In 2007 the Museum of London Docklands at Canada Water opened a permanent gallery, ‘London, Sugar and Slavery’. Amongst the extensive information on the anti-slavery campaign is a display of teapots and bowls overprinted with anti-slavery messages, and in the section on women campaigners you can see a pamphlet printed in 1828 for the Peckham Ladies African and Anti-Slavery Association.

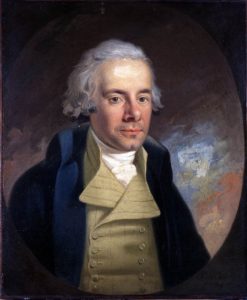

William Wilberforce (1759-1833)

The Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade had been formed in 1787 by a group of Evangelical English Protestants and Quakers, united in their shared opposition to slavery and the slave trade. William Wilberforce MP was a leading campaigner.

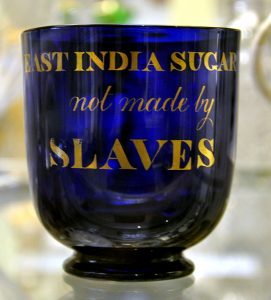

One of the consumer actions was the boycott of West Indies sugar. East Indies sugar was promoted as though more expensive it was produced by free labour rather than slave labour. There were two periods of boycott campaigns: 1791-1792 and 1825-1829. William Fox published an anti-sugar pamphlet in 1791, the same year that Wilberforce’s first abolition bill was rejected. It sold 70,000 copies in four months. Cartoons depicting King George lll and his family reinforced the message. By 1792, about 400,000 people in Britain were boycotting slave-grown sugar. Sugar sales dropped by over a third.

In 1807 the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act made it illegal to engage in the slave trade throughout the British colonies – but the practice of slavery continued in the West Indies. So the sugar boycott was revived in the 1820s.

As before, the campaigns were primarily supported by the female anti-slavery associations. With no vote to influence politicians they could only resort to publicity and practical action.

Newspapers ridiculed the campaigners. They tried to put them in their ‘proper’ place. One such article appeared in the Leicester Journal on 30 October 1829. The author is anonymous (‘from the John Bull’) but his tone is patronising from the start:

Where Peckham exactly is situated, we cannot take upon ourselves to say, but we have reason to believe that it lies somewhere between Deptford and Camberwell; and we must say, the female natives appear to be of an uncommonly amiable turn of mind. They held a meeting, which they tell us, was conducted with much harmony and good will. . . .’

He then goes on to describe the resolutions passed; the first of which was:

That under a deep conviction that the system of Slavery is wholly inconsistent with the principles and precepts of Christianity, we form ourselves into a Society, to be called the Peckham Ladies’ African and Anti-Slavery Association; whose object shall be, to assist in promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Education of African Children.

Later resolutions concerned the administration of the association, committee, meetings and subscriptions. One objective was Resolution 5: ‘That the Members of the Association be earnestly recommended to adopt the use of East India Sugar ; and to discourage, by every prudent means in their power, the use of West India, so long as it is the produce of Slave labour.’

The journalist may have missed his target. To any supporter of the campaign this was all good publicity – clear objectives of a well-organised group, activities reminiscent of the suffrage campaigns at the end of the century (and with a similar response from the media).

The author then decides to ‘publish, for the honour of the ladies, for the gratification of their husbands, and for the edification of the empire of Peckhamia, the names of the Council.’ To embarrass them?

Mrs Cash, The Treasurer [from ‘He is Our Cousin, Cousin: A Quaker Family’s History from 1660 to the Present Day by Antony Barlow (2015)

They include Mrs Elizabeth Petipher Cash (1796-1894), Elizabeth and Mary, the daughters of Mary Dudley and Mrs Frances Naish, wife of William Naish (1785-1860). He was the author of the pamphlet Reasons for Using East India Sugar. (Peckham Society News, PSN 154, Autumn 2018). The Savory daughters from Alfred House in Peckham Road (later to become Camberwell House) were also members.

As if this was not enough, our author makes a cheap joke about their names:

It will be perceived that this community has so strict a regard to propriety that Mrs. Cash is appointed Treasurer, Miss Read, Secretary, — (why not Miss Wright?) — Miss Post, no doubt, despatches the circular letters, and Miss Pace walks round to deliver them ; Miss Savory prepares the refreshments, while Miss Harvey furnishes the sauce. The duties of Mrs. Rutter, and the rest of her fair colleagues, we do not presume to decide upon, but we have no doubt that the whole nineteen are as agreeable, good, well-meaning bodies, as ever met. They are the very pick of Peckham, and Peter Piper himself could not have picked a prettier peck.

He goes on to describe how they set about their work, visiting every house in the district to present their arguments, gaining subscriptions and selling merchandise. The latter comes in for a lot of ridicule as do the accounting procedures of ‘this silly society’ – though again they demonstrate how well-organised the group is. He has difficulty comprehending the purpose of some of the merchandise such as a ‘match pot’ and makes fun of the descriptions:

He goes on to describe how they set about their work, visiting every house in the district to present their arguments, gaining subscriptions and selling merchandise. The latter comes in for a lot of ridicule as do the accounting procedures of ‘this silly society’ – though again they demonstrate how well-organised the group is. He has difficulty comprehending the purpose of some of the merchandise such as a ‘match pot’ and makes fun of the descriptions:

There are earthenware match-pots at five shillings and sixpence a pair, and drinking mugs from 4½ d. to 2s. each — articles of equal curiosity with reading files or dining tables.

John Bull does succeed in making one interesting point, forgotten today in our busy world of instant media: that amongst the houses visited by the group were ‘the Poor, whom the Visitors found to be very ignorant of the cruelties of Slavery, and, in some instances, even of its very existence.’

We would recommend these good ladies, who like those of the neighbouring state of Clapham, have thought proper to try at notoriety by exposing a vulgar and senseless cry, to devote themselves to the respective duties of their own lives, to attend to the wants of their poor neighbours, of whose necessities and claims they may fairly judge ; to look after their own little household affairs ; to treat their servants — if they have any — as well as the West India planter treats his slaves, and leave the regulation of great national questions to the Government, which upon the matter particularly interesting to them possesses quite enough of cant, quackery, and old womanism, in the Colonial department, without the interference of Mesdames Cash, Post, Pace, Rutter and Co. of Peckham and Rye.

A Ladies’ Committee – not our Peckham ladies, but a ‘Meeting of the Ladies committee for the Great Exhibition 1851’, by Mary Lightbody Gow (1851-1929) from The Life and Times of Queen Victoria.

Overall the article is a good summary of the activities of the group and demonstrates the sort of prejudice they had to overcome; it is a forerunner of the campaign for the emancipation of women.

It says more about the narrow prejudices of the journalist: an accomplished satirist he is not.

Christine Camplin

Reprinted from Peckham Society News, Issue 155 (Winter 2018)