Home to the Spitta family

Peckham House, demolished in 1954, probably dated from the 18th century. It was situated on land now occupied by the Academy at Peckham, with fine gardens stretching almost as far south as what is now Highshore Road. There is a well-known reference to it in Blanch’s Ye Parish of Camerwell, which tells us: “The wealthy family of Spitta lived here in great style, giving fêtes, or what would now be termed garden-parties, to their neighbours, and dispensing charity with no niggard hand amongst the poor of the locality.”

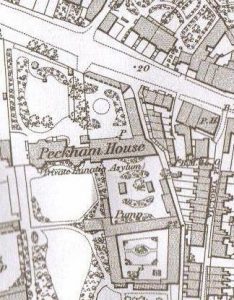

Peckham House, 1871

Blanch also records the birth, on 28 February 1785, of Catherine Spitta, daughter of Charles Lewis and Ann Spitta, who lived in “the fine mansion in the Peckham Road”. Charles Lewis was almost certainly Carl Ludewig Spitta, a native of Braunschweig (Brunswick), Germany, born on 24 December 1747, who moved to England as a young man and became a naturalised British subject in 1775. He later became a partner in a business in Lawrence Pountney Lane which features frequently in the business reports of The Times in the early years of the nineteenth century. A son, Robert John, born to Charles Lewis Spitta and Mary Spitta (presumably his second wife) and baptised at St. Giles, Camberwell, on 31 March 1815, qualified as a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries of London in 1841 and became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1842. Through two succeeding generations, descendants of Charles Lewis would become famous and distinguished medical practitioners, although not in Peckham.

A change of use

On 29 May 1824 Peckham House was put on the market. The advertisement in The Times described it (accurately) as “a most respectable and commodious residence”. But it must have been difficult to sell because it is generally accepted that it was not until 1826 that it was acquired for development as a private asylum for mentally ill people, with the house itself set aside for private patients and with outhouses for paupers. This was typical of a growing trade in ‘private’ asylums. Notwithstanding efforts to build public asylums and to improve regulation, private provision offered rich pickings, particularly by accommodating disturbed paupers. As the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy acknowledged, the Peckham asylum had advantages in that the site, grounds and internal accommodation were good, but beyond this much depended on the proprietor. ln this respect the functioning of Peckham House was initially in the hands of a particularly controversial figure.

Charles Mott

In 1829 Peckham House was initially licensed to accommodate 172 pauper patients and 40 private patients. According to a prospectus put out in 1827, now held by Southwark’s Local History Library, the joint proprietors were “Mott and Parsons”, the latter perhaps having been previously involved in Parsons’ Peckham Retreat. But, describing himself as the principal proprietor and half owner of the new Peckham asylum, Charles Mott was undoubtedly in control.

Andrew Roberts, whose resource website at www.mdx.ac.uk has extensive coverage of the trade in pauper lunacy, notices that Mott considered it vital that the manager should have a financial interest in achieving “the small savings which make the difference between economical and extravagant management”. It is absolutely clear that the diet at Peckham was meagre. Mott was a man of extreme parsimony, a mindset of which he made no secret; indeed one that he evidently regarded as a virtue. As manager of Lambeth’s poor law from 1831, his approach to the maintenance of poor people in Lambeth’s workhouse was to cut costs by a third, making savings of £3,000, principally by the food “being given out in more exact proportions”. He was opposed to what he called “the tendency to a constant increase of diet and accumulation of comforts from the interference of and influence of humane but mistaken individuals”, remarking upon a county magistrate who had given small parcels of tea to a number of the old inmates at Lambeth workhouse and had recommended an allowance for the “comforts” of tea and sugar to elderly paupers. As a result, and despite Mott’s protests, 95 elderly inmates had been allowed 6d each week in addition to their allowance of food, costing the parish over £125 a year. “Humane individuals,” Mott declared, “rarely calculate upon the tendency or aggregate effect of such alterations”. Had it not been for his contractual control, he suggested, the indulgence would probably have been extended to the greater proportion of the inmates. On the contrary, Mott considered that the diet, besides being uniform in amount, should be uniformly reduced in quantity and quality. When he discovered that the workhouse scales were half an ounce out in favour of the paupers (due to an accumulation of dirt on the side of the weights), he had the scales scrubbed and adjusted “with nicety”, annually by a scale maker and daily by those who used them. Astonishingly (or perhaps because of his niggardly doctrine), Mott was appointed an Assistant Poor Law Commissioner in November 1834, work which took him away from Peckham and eventually ended in disgrace.

A “source of trouble”

In 1843 Peter Armstrong, who from the outset had been responsible for the day-to-day management of Peckham House, announced in The Times that “a new and handsome set of apartments” had been added to cater for a second and third class of private patients. “The house,” he said, “is delightfully situate, on the road leading from Camberwell to Peckham…where the air is well known for its mildness and salubrity.” Despite this, however, Peckham House remained one of only three metropolitan establishments receiving paupers, with as many as 251 housed there, and the main problem that vexed the Commissioners was the insufficiency of their food. Mott’s spirit appears to have lingered for some time after his physical presence had departed. In 1844, the Commissioners commented that the diet of the pauper patients had “always been a source of trouble”. Their report to the Lord Chancellor admitted: “lt may be asked if we have not been too lenient in renewing, from time to time, the licences for Peckham and Hoxton Asylums. Your Lordship, however, must be aware, that in consequence of the deficient accommodation in public asylums, if licences were withdrawn from houses containing a large number of paupers, there would be no alternative but to send the patients to workhouses or to board with other paupers, where they would not have the care which they now receive under regular visitation and supervision”.

A famous visitor

One such visit, on 18 November 1844, was made by no less a person than Lord Ashley (later the seventh earl of Shaftesbury), who spent six hours at Peckham House. ln his diary he reflected on what he saw as the tiny gap between reason and madness, musing that he was then visiting in authority, yet tomorrow could be one of those visited by authority. But he thanked God that there were any visitations at all; time was when such care was unknown. In the following year, after a lengthy inquiry, he was prominent in securing passage of the Lunacy Act 1845 which, with a new County Asylums Act, was intended to strengthen the provisions of earlier legislation.

In October 1848 Peckham House became the first private asylum in London to experience an outbreak of cholera. By 1859 it remained one of five licensed houses in the metropolitan district — all of them large establishments – to cater for paupers. The number of patients — of both sexes — had then reached 367 – 317 paupers and only 50 private patients. By this time the licence had passed to Peter Armstrong’s son, Dr Henry Armstrong, and Samuel Morris, a surgeon, and it was not until 1866 that the Commissioners again found cause to comment “very unfavourably” on the condition of Peckham House. Even this criticism was short-lived. In the following year the Commissioners reported that “the general condition of the establishment had on the whole improved”. That improvement took a decisive forward step in February 1872 when Dr Alonzo Henry Stocker succeeded Dr Armstrong.

Under new management

Stocker, born in Stoke Damerel, Devon, in 1830 was a licentiate of the Apothecaries‘ Society (1851), a member of the Royal College of Surgeons (1852), a doctor of medicine (St. Andrews, 1855) and a member of the Royal College of Physicians (1860). Before moving to Peckham House, he had gained significant experience as the superintendent of

Grove Hall asylum at Bow.

Assisted by Mr Brown (medical superintendent) and Dr Barringer (medical officer), Stocker set to work to improve the facilities at the Peckham asylum, but soon faced an unforeseen setback. On a Saturday afternoon early in November 1873, on opening a cupboard in a room on the third floor, he was met by flames and smoke. The fire spread rapidly but, despite injuries to his face, Stocker was able to move the patients affected to a place of safety. The damage, estimated at £1,500, was considerable, gutting several rooms of the house and destroying the roof.

Stocker nevertheless turned the misfortune of the fire to advantage, taking the opportunity to make improvements in the house and adding a “neat and substantial building adjoining the entrance gates” for use as a lodge. Evidently he was a man of significant means because in 1874 he also purchased a large and imposing mansion, Craigweil House at Aldwick, near Bognor Regis, which was later to serve as the residence where King George V was able to recuperate from a near-fatal illness.

Life within asylums at this time was largely unseen, but in the case of Peckham House we have the benefit of a fascinating account of a guided tour in 1874 by a special correspondent of the Circle periodical, who concluded that “Dr Stocker’s asylum may fairly be compared with any similar establishment in the kingdom. The unfortunate patients are treated with the utmost kindness and attention. Their whims and delusions are humoured, and no restrictions are exercised, except where absolutely necessary.” Every patient was visited once or twice a day by the doctor, and while wines and spirits were allowed only as “medical comforts”, smoking could be freely indulged in. A service was held every Sunday afternoon led by the Rev. James Hazell, and a ball was held every Monday evening, with dancing for two hours. Occasional magic lantern shows, concerts and other entertainments were held during the week. “ln fact,” the reporter concluded, “nothing that can tend to ameliorate the medical condition of the patient is left undone.”

Celebrated connections

As the provision of public asylums increased, so the housing of pauper patients in private asylums gradually declined. Over the years, Peckham House became “a private hospital for the treatment of patients suffering from nervous and mental illnesses”. Back in 1874, Blanch said that the residents of Peckham House were “drawn from all classes of society — from the pauper inmate to the titled dame”, and the article in the Circle magazine refers, intriguingly, to a famous opera singer, “Madame C.”

There is absolutely no reason to doubt that the asylum received members of the “great and good” as private patients, but just who they were is generally lost in the mists of time, most patient files having long since been destroyed. In only a few famous cases do we know something, from other sources, of the circumstances of their admission to Peckham House. The comedian Dan Leno (1860-1904), whose mental decline has been thoroughly documented, was admitted in 1903. Listening to his 1901 recording of The Beefeater (admirably clear for its age) one may feel that his style was already close to raving.

Another victim of mental illness was Hannah Chaplin, mother of the comic genius Charlie. Though hardly as famous as her son, she had briefly been a vaudeville artist (as Lily Harley) until her voice failed. lmpoverished and malnourished, she alternated during Charlie’s youth between shabby rooms in Kennington, Lambeth Workhouse and the public asylum at Cane Hill, Surrey. In 1912, Charlie — by this time making his name with Karno’s Company in the USA – and his brother Sydney visited her at Cane Hill and found that she had been confined to a padded room. Sydney saw her and discovered that she had been given the shock treatment of icy cold showers and that her face was quite blue. They decided to put her into a private institution and she was admitted to Peckham House on 9 September of that year. She had been a patient there for nearly three years when the proprietors felt obliged to place her on the “Parish Class” because the brothers Sydney and Charlie — the latter by then having appeared in 42 films — had defaulted in paying the fees of 30 shillings per week! Criticism of the brothers has perhaps been harsh, because the Peckham House receipts show that Hannah’s sons had generally been conscientious in making payments. It appears that only the pressure of their work and the uncertainty of wartime mails across the Atlantic led to some irregularity.

The final phase

Provision within the asylum steadily improved and photographs in a brochure held by Southwark Local History Library, thought to be from the 1920s, testify to a well-run and in many parts opulent establishment. Dr. Alonzo Henry Stocker, who had lived there with his family, died on 24 April 1910, leaving a gross estate of £123,993, to be succeeded by a family partnership. The 1919 Post Office Directory gives the “resident licensees” as Alonzo Harold Stocker and Hubert Goodman Stocker. The family connection continued until 1952, the last owner being Dr Rupert Stocker, grandson of the first licensee.

It is said that heavy death duties on Alonzo Harold Stocker and his wife forced the family to put Peckham House on the market. The South London Press commented on the plight of 130 “old folk” who would lose their homes on the closure of the asylum. Some of them had been there for many years; in one case since 1890. Many of them, commented Rupert Stocker, had no living relatives. They paid a very moderate sum for accommodation and medical treatment and could not afford the high fees in most private mental homes, anything from eight to 15 guineas a week. Nevertheless, the London County Council saw the availability of the property and spacious grounds as an irresistible opportunity. The LCC minutes of 4 March 1952, noting that the owners intended to dispose of the property, saw the six-acre site as ideal to secure a more favourable location for a new school. The cost of acquisition, clearance and partial redevelopment would be in the region of only £100,000. Sadly, in those less enlightened days, planning consent was given for a change of use, and the grand historic mansion was demolished two years later. One of the last remnants of Peckham’s historic heritage was almost casually lost.

As far as I have been able to ascertain, all that now remains of Peckham House is its magnificent staircase. This has had a remarkable and somewhat fortuitous recent history. When the house was demolished, its staircase passed into the warehouse of the Ancient Buildings Section of the London County Council and might have remained there but for a fortunate enquiry in 1956 from Fulham Palace. The architects there wondered whether the LCC might have in store a staircase of suitable character to be used in a scheme to develop the See House at the Palace. After numerous ad hoc arrangements to provide for successive Bishops of London, it had been decided to adapt accommodation near the chapel in the south eastern quarter of the Tudor courtyard, to include a dining room at first floor level. What was needed was a fine staircase to connect this new room with the principal ground floor reception rooms. The unwanted staircase from Peckham House fitted the bill exactly and was purchased for only £30. With minimal adaptation, it was incorporated so perfectly that it seemed to have been originally designed for its new location.

Nearly fifty years later, in 2005, further refurbishment work led to the staircase being carefully removed, permission to do so having been made subject, among other things, to the method of its dismantling and storage being agreed with the relevant authorities. Despite being offered for disposal through the Museums Journal there were no takers and the last remnant of Peckham House, at the time of writing, remains stored at Fulham Palace.

So perhaps the story of Peckham House may have a final happy ending.

Derek Kinrade

Reprinted from Peckham Society News, Issues 115 (Spring 2009) and 116 (Summer (2009)

Sources

I acknowledge and have been particularly helped by the resource website of Andrew Roberts at www.mdx.ac.uk and by the unstinting help of the Braunschweig Stadtarchiv.

A fascinating account of the life of Charles Mott can be seen in David Hurst’s A ticklish sort of affair (History of Psychiatry, vol.16, 2005).

See also: Lost Hospitals of London: Peckham House

Footnotes

In September 1873 the parish of Camberwell had 264 [pauper] lunatics and imbeciles in asylums, and 113 of these were at Caterham Asylum.

The parish contained two private asylums: Peckham House and Camberwell House.

Ye Parish of Camberwell W.H. Blanch (1875)

of Camberwell W.H. Blanch (1875)

Middlesex pauper lunatics – showing where they are kept

1. 567 are in Licensed Houses – 3 of them at Messrs. Parson’s Peckham Retreat

2. 286 are in workhouses

3. 19 with friends

London Evening Standard, 9 November 1827