Arson in Nunhead

George Clift (born 1837) and Frederick Layton Clift (born 1839) were the youngest sons of Isaac Clift and Sarah Ann Layton. Isaac was a skilled cordwainer in Islington with several employees. After he died in about 1840, Sarah married William Lanham, a tiler and plasterer and moved to Westbury, Wiltshire in 1848. By the 1851 Census Frederick was still at school but 13-year-old George had returned to London and was an apprentice Artist Brush Manufacturer in Islington.

Both brothers were well-educated and become independent tradesmen. George Clift married Mary Ann Jane Kemp in 1857 in Clerkenwell and after their first two children, George and William, were born the family moved to Peckham. In 1861 they were living at 7 Gloucester Terrace, Camberwell, George was a ‘Brush Manufacturer Master’ employing two boys and they had had a further son, Frederick James Clift. Frederick Clift married Emily Moore on 23 April 1859 and by 1861 the family had moved to Peckham, where their only son Frederick William was born, and were living at Hannah Cottages, 2 Commercial Road. Frederick was a quill merchant. He had a government contract to supply a large quantity of quills for the Armstrong guns manufactured at Woolwich Arsenal. These breech-loading field guns, designed by Sir William Armstrong in 1855, were fired by placing a goose quill filled with powder into the vent. Only low-quality goose or duck quills were used; the more expensive swan quills were reserved for writing.

Unfortunately, it appears that brothers then decided that their income from the brush and quill trade was insufficient and it was time to supplement it by some other means.

On 13 or 14 July 1860 Frederick Clift rented a house at 2 Lansdowne Villas, Albert Road, Peckham, from Mr John Pullar, a builder, for £30 per annum. The house had a stable attached to it, which Frederick said he needed for his horse and trap – he currently had to stable his horse at his brother’s house in Harders Road. He neglected to say that he really wanted to use the stable as a warehouse.

The following week on 20 July the brothers went to the offices of the Globe Insurance Company where Frederick requested £2500 insurance on his stock of quills (at least £200,000 in today’s values) and £300 on his household furniture. He had never felt the need for insurance before. Fortuitously for the company William Collis, one of their clerks, happened to live in the adjoining house so they asked him to inspect the premises before agreeing the policy. Frederick showed him the furniture in the downstairs rooms and the stable filled to the roof with large sacks and bales of quills. Collis could see no doorway between the house and the stable which reduced the risk of a household fire spreading to the valuable stock. The policy was duly granted for a premium of £7 14s.

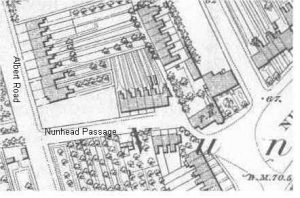

Nunhead Passage was later renamed Scylla Road; Albert Road was renamed Consort Road.

Nunhead passage runs west from the Nunhead Tavern (‘PH’ on map ) to Albert Road, and crosses it. ‘There is a hedge on one side of that passage and a bit of garden ground between that hedge and 2 Lansdowne Villas. A garden ran round the premises. Between Nunhead-lane and the passage was a piece of vacant ground belonging to the landlord.’

Between nine end ten o’clock on the evening of the 2nd of August George Clift was seen at the Nunhead Tavern on Nunhead Green by William Collis’s brother. George left the tavern, walking towards of the house. A few minutes later PC Edward Cox, on duty in Nunhead Passage, saw a man resembling George come through a gap in the hedge behind the house and walk quickly towards the main road ‘as a person might run if they were trying to overtake an omnibus’. Others saw him emerge from the passage too: Frederick Goodwin, son of Samuel Goodwin, a grocer in Nunhead saw him under a bright gas lamp, but could not tell if he had gone into the Edinburgh Tavern. Joseph Brindle, who lived at Nunhead Lodge at the corner of Albert Road and Nunhead Lane was in his water-closet at the side of his garden. He heard a sound like a ‘plate thrown at the fruit tree’, and heard someone running away. After the fire had subsided he found a candlestick lying on the path which he handed in to the police.

Suddenly the alarm went up: the stable was on fire! William Johnson, landlord of the Nunhead Tavern, sent his potman Robert Ling and one or two others out to help. The men focused on the house, carrying furniture out to the almshouse gardens opposite. Ling ran to rescue the horse, removed some roof tiles and saw that the stable was comparatively empty and was on fire in two places. The fire spread quickly to the house; Ling ran upstairs to check if anyone was trapped. Directly after he came down again the stairs fell in.

The Old Nun’s Head, c.1930

By the time the fire brigade arrived about 11 o’clock the house and premises were entirely gutted. They examined the damage over the next few days and concluded that the fire had been set in two places, and had started where a doorway had been broken through between the house and the stable.

John Pullar, the landlord of the house, was not pleased that his property had been ‘modified’ without his permission, nor that the stable had been used for storage of goods. The remains of a large quantity of very cheap quills were discovered, but little evidence of the vast stock of high-quality swan quills described in the insurance policy. The fire officers later stated that it was very difficult to destroy quills and feathers completely.

Frederick subsequently put in a claim setting forth his losses as £4000. The insurance company were suspicious, the claim was refused, and the brothers were arrested.

George Clift and Frederick Clayton [sic] Clift were charged with ‘Feloniously setting fire to a certain house, with intent to defraud the Globe Insurance Company’. The trial took place at Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey on 21 October 1861 before Judge Baron Wilde. At the trial both men were described as quill merchants. (From this point on Frederick’s second name was to be written as ‘Clayton’.) The case ran on until late evening and involved the examination of a large number of witnesses. Amongst the final witnesses were Thomas Shorn and Edward Boulton, carmen. They testified that they had carried bales of quills away from the house in Albert Road a few days before the fire.

Frederick claimed that they had gone to Waltham that afternoon, and not returned until 11.30. He could not account for the fire. The house was empty as they had dismissed the servants the week before, and his wife had taken their sick child to a doctor in Southampton Street that evening.

Defence lawyers claimed the evidence was merely circumstantial. However, neither defendant produced any witnesses in their defence. The jury retired, returning after only a quarter of an hour with a verdict of guilty against both prisoners but recommended them to mercy on account of their respectability and youth.

Judge Wilde, in passing sentence, said that they had been found guilty of one of the most heinous offences that could be committed in a civilized community, jeopardising the lives and property of others for ‘mere filthy gain’. A few years earlier they would have forfeited their lives. He felt that their education and position placed them above those who had not enjoyed similar advantages and sentenced them both to ten years penal servitude – transportation.

Frederick Clift dramatically protested his innocence, calling upon Christ and His angels. He said his brother was innocent, and that they had sixty witnesses who could swear that his brother was playing skittles at the time. George Clift, though visibly affected, said nothing.

The brothers were returned to Millbank prison to await transportation. On 15 December Frederick was back at the Old Bailey charged with ‘Feloniously being at large before the expiration of the period to which he had been sentenced.’ Warder Dennis Howard stated that the prisoner, with two others, had broken out of the prison, by bribing one of the warders. His sentence was increased from 10 to 15 years. Frederick was moved to Chatham Prison and George to Portsmouth.

The journey to Australia took almost 10 weeks. George Clift left Portsmouth on 11 March 1863, one of 320 convicts on the Clyde and arrived at Fremantle, Western Australia, on 29 May, 1863. An entry in the Male Prisoners Property Book lists his meagre possessions: three books, tracts, letters, one photograph, a Hymn Book, Manual of Prayer and Broken Photograph Box. Other convicts had nothing more than a toothbrush or a hymnbook – or ‘Nil’. Frederick Clift followed from Chatham Prison on 14 June 1864 the following year, one of 260 convicts on the Merchantman, and arrived at Fremantle on 12 September 1864. George arrived in middle of winter; Frederick in spring. They were soon to experience the harsh Western Australian summer temperatures.

Convict records give some idea of the brothers’ physical appearance. Frederick (prisoner no.7951): age 26, 5′ 4″ tall, brown hair, hazel eyes, thin visage, sallow complexion, middling stout build, lost 2 front upper teeth, rather deaf; George (prisoner no. 7043): age 28, 5′ 4″ tall, light brown hair, hazel eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, middling stout build. Both could read and write well, were of Very Good Character and were protestants; George was an artist and brushmaker and Frederick a brush manufacturer. (No quills?) By then Mary Ann Clift had downsized to 5 Hill Street, Peckham and Emma Clift to 1 Mimosa Cottage, Mason Street, New Cross.

The first British penal colony had been established in Australia in 1787 at Port Jackson, Sydney, and convicts were initially sent to the east coast of Australia until the discovery of gold made this too attractive. However, the fledgling colony south of Swan River, Western Australia needed a supply of physical labour for the farms and town construction so between 1850 and 1868 9,668 British convicts in 43 ships were sent there. (By 1868 the British government had transported about 162,000 convicts to Australia overall.)

Fremantle Prison was completed with convict labour in 1859. It followed the design of English ‘Model Prisons’ such as Pentonville, which focused on reform rather than punishment; ultimately the convicts would have to be integrated into the local community. When not working they were held in individual cells with long periods of isolation and silence. During the day many worked on building and road projects in Fremantle and Perth. The Main Cell Block was designed to hold up to 1000 convicts, though there were just over 200 by the 1870s, and there was a hospital as they needed a healthy labour force.

The convict establishment, Fremantle, Western Australia, watercolour by T.H.J. Browne, 1866 (http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au)

It is not known if George worked as an artist but he was probably gainfully employed as a brushmaker. He became eligible for his Ticket of Leave on 6 March 1865, less than two years after arrival, and as his behaviour both on the journey and on land was exemplary, this was granted. Tickets of Leave, granted as a reward for good behaviour, enabled convicts to seek employment within a specified district, though not leave it without permission. If they kept to all the rules they were entitled to a conditional pardon after completing half of their sentence. They were then treated as a free person though could not leave the colony until the full sentence had been served. I have not yet been able to find out if either brother achieved this.

Frederick was still the impetuous rebel brother. He became eligible for his Ticket of Leave on 12 April 1867 but this was not discharged until 19 March 1868. He was reported and punished for a number of minor offences such as: Not reporting place of abode (5/5/1872) – fined 10/-; Absent from master’s service (25/1/1873) – 1 month extension; Dirty & untidy cell (22/1/1873) – cautioned; Absconding from the Swan District (17/2/1874) – 2 month extension. He had a range of jobs such as gardener, labourer, driver and gentleman’s servant in locations including Fremantle, Jarrah Dale and Pinjarrah.

Convicts were paid and sent money home: Frederick received a cheque for £2.6s.8d for February and March 1873. In the 1871 Census his wife Emily, living at 12 Coopers Road, Camberwell, was receiving ‘Remittance from husband in Australia’. Meanwhile Mary Ann Clift, wife of George had moved to 2 Burts Cottages, Camberwell and working as a Dress Maker. 11-year-old George was already out working as a Painter’s boy. Both wives had 27-year old boarders: Emily Clift’s was Robert Sinclair, a commercial clerk, while Mary Ann’s John Flentey was a painter. Their household also included a daughter, 1-year-old Mary Clift, born in France in 1870.

Back in Australia, Frederick Clift’s name appeared on the Casual Sick lists for ‘varicose veins’ on 24 February 1876 and by 28 October he was being treated for ‘swelling in leg’. In early 1877 he was in Fremantle Prison Hospital, the ‘Imperial Invalid Depot’, where at the end of March his leg was amputated at the thigh. This did not halt the progress of the disease and he died on 30 April 1877. On 1 May 1877 it was ‘certified that Reconvicted Prisoner Reg. No. 7951 Frederick Clift who was admitted to Hospital on the 3rd May 1876 with a (Tumour) died last evening at 11.50 from Medullary Cancer.’ He was 41. George Clift’s end is a little more enigmatic: a single reference to cause of death as ‘Drowned from a coaster’ in 1872 aged just 36.

Sadly I have been unable to find out whether the Peckham brothers, after their fraternal venture into crime, ever managed to meet up in Australia. Their wives and children also ‘disappeared’ from records. If any members have further information please do contact me.

Christine Camplin

Sources

www.oldbaileyonline.org Trial of George Clift, Frederick Clayton Clift. bit.ly/PSN148p24a

The Sydney Morning Herald, Thu 13 Feb 1862 ‘Conviction And Punishment Of Two Incendiaries.’

Dictionary of Australian Artists Online (www.daao.org.au)

www.convictrecords.com.au

Reprinted from Peckham Society News, Issue 148 (Spring 2017)